Friends, today I have a saga to share with you, one that fortunately ends happily: with a crusty, open-crumbed loaf of ciabatta bread, the recipe for which I hope you make soon and then all summer long, for beach lunches and mountain hikes, for dinner with friends and family, perhaps beside a fire or under twinkling bulbs strung from tree to tree, a pool of olive oil at the ready to dunk into at will. This has become one of my favorite homemade bread recipes. Grab a cup of tea, let’s start from the top … After posting this sourdough ciabatta bread recipe in April, I felt determined to make a comparable, yeast-leavened variation. For reasons I cannot explain, when I revisited a recipe I had posted here years ago, the photos for which looked promising, I couldn’t get it to work quite as well. The rolls, while tasty, had a tight, closed crumb, not as light or as open as I remembered (or as pictured). In search of that more wild, amorphous crumb, similar to that of a homemade baguette, I turned to my various bread baking books, namely The Bread Baker’s Apprentice, which noted that ciabatta often is made with a poolish or biga, meaning a small amount of flour and water mixed with a leavening agent and left to ferment for a short period of time. This got me thinking: could I replace the 100 grams of sourdough starter in the sourdough ciabatta recipe with 100 grams of poolish? I gave it a go, stirring together 50 grams each flour and water with 1/2 teaspoon instant yeast and then letting it sit for three hours. When the surface of the poolish was dimpled with holes, I proceeded with the recipe, adding water, salt, and flour; mixing the dough; stretching and folding it; letting it rise, and finally transferring it to the fridge overnight. The following morning, I turned the dough out onto a floured work surface, cut it into eight portions, and transferred them to a sheet pan. One hour later, I baked them. Friends! It worked beautifully. The crumb, while not quite as honeycombed as the sourdough version, was full of holes, giving the ciabatta its characteristic lightness and airiness. I felt really good about the recipe — it was simple enough, nearly identical to the sourdough version without having to use a sourdough starter, and very tasty. I almost posted the recipe but anticipating that some people might want a loaf of ciabatta as opposed to rolls, I decided to test the recipe in loaf form. This is where the saga begins. The two loaves I pulled from the oven, while crusty and beautiful from the exterior, were … HOLLOW! I had baked, in essence, two gigantic pita breads, perfect for housing torpedo-sized falafel. (Stay tuned … the saga continues! Kidding.) This experience sent me on a tear to figure out where I went wrong. As I read about “tunneling”, I tried many things to fix the situation — lowering the hydration, increasing the hydration, kneading the dough, lowering the oven temperature, decreasing the amount of yeast, eliminating the cold proof — and in the process, I made many many loaves of hollow ciabatta. At the risk of sounding a little dramatic, this quest paralyzed me creatively — truly: without this ciabatta puzzle solved, I couldn’t create a single new recipe for the blog. In the end, after doing a bit more digging, the fix was simple: to lengthen the final proof. Whereas the sourdough ciabatta can rest at room temperature for only an hour before baking; the yeasted ciabatta — at least in loaf form — needs much more time, more like 2 to 2.5 hours. Why? Because, as I’ve learned, when under-proofed dough enters an oven, the yeast has lots of remaining energy, which leads to fast and furious gas production. This explosion of gas breaks the structure of the bread, causing the tunnel to form. As soon as I extended that room-temperature proof, the tunnels, thankfully, vanished. Friends, if I’m being honest, it is not without trepidation that I post this recipe. As I type, I have two bowls of ciabatta dough rising — just to be sure! I have made more ciabatta these past two months than any other bread I think ever (with the exception, of course, of my mother’s peasant bread), and though I am now consistently met with great results — with loaves that emerge from the oven flour-dusted, golden-crusted with both a chewy and light, porous texture — I still worry. Those hollow loaves haunt me. As you can see, I’m a bit anxious for you all to give this recipe a try. My wish, as noted at the start, is for this to become your summer dinner bread, your trusty swiper for all those delicious, oily, corn-studded, tomato-infused, basil-specked dregs. They deserve it. If you give it a go, please let me know how it turns out. PS: Foolproof Pita Bread Recipe PPS: Overnight Refrigerator Focaccia = The Best Focaccia

Traditional Ciabatta: An Overview

Let’s review what ciabatta is:

Traditional ciabatta is characterized by a slipper shape as well as an extremely porous and chewy texture. Originating from the Lake Como region of northern Italy, ciabatta means “slipper” in Italian. Ciabatta dough is wet and sticky with hydration levels often 80% or higher. Both the recipe below and this sourdough version are 82% hydration. (If you are unfamiliar: To calculate hydration percentage, simply divide the weight of the water by the weight of the flour; then multiply it by 100. In this recipe, that’s 410/500=0.82 | 0.82 x 100 = 82%) Traditional ciabatta recipes call for very little yeast and a long, slow rise. Many recipes call for making a biga or poolish (as noted above), which helps produce that light, airy texture. Some ciabatta recipes call for milk or olive oil, but neither of these ingredients is required to make a traditional loaf of ciabatta.

And let’s review what ciabatta isn’t:

Shaped! In the ciabatta bread recipe in Jeffrey Hamelman’s Bread, he notes: “There is no preshaping or final shaping—once divided, the dough is simply placed onto a floured work surface for its final proofing.” With the sourdough ciabatta bread recipe, I follow this no-shaping rule. In this yeasted recipe, I deviate! After a number of experiments, I prefer doing a pre-shape — it’s counterintuitive but I actually get a more open crumb when I preshape the dough. That said, for ciabatta rolls, I stick to the no-shaping rule — it’s nice not having to ball up 8 portions of dough. (Of course, you can experiment and see which method you like best.) Scored! Unlike other crusty loaves of bread, ciabatta is not scored.

Troubleshooting

If your dough does not cooperate the first time around, you may need to make some changes:

Water: This is a very high-hydration dough, and depending on the flour you are using and your environment (if you live in a humid environment, for instance), you may need to reduce the amount of water. If, for example, when doing your stretches and folds, the dough never came together in a cohesive ball, I would reduce the water by 50 to 60 grams next time around. Flour: All flours absorb water differently. Through troubleshooting with people all over the world often with people making this sourdough pizza recipe, this yeast-leavened pizza recipe, and most recently this sourdough ciabatta recipe, the type of flour being used plays a critical role in how the dough turns out. Often the water needs to be reduced considerably for the dough to come together. If you live abroad or in Canada, you can either make the recipe once as written or add the water slowly, mixing as you do, until the dough resembles the dough in the video. Shaping: Because this is such a wet dough, shaping may be tricky. I have smooth, wooden countertops (there’s some sort of sealant on top) that work nicely for shaping, and I imagine granite and marble would work well, too. My mother loves her Roul’ Pat for shaping. All of this is to say, if you are having trouble shaping, the surface you are shaping on could be playing a role.

How to Make Ciabatta Bread, Step by Step

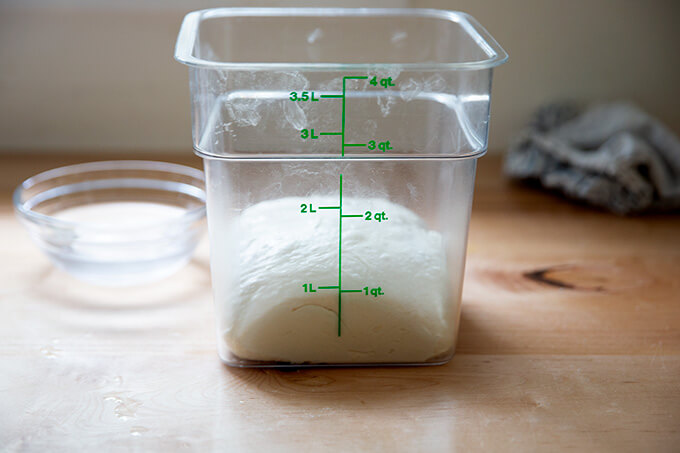

The first step of the recipe calls for making the poolish. To do so, gather your ingredients: flour, water, and instant yeast. SAF is my preference. Whisk together 50 grams flour and 1/2 teaspoon instant yeast. Add 50 grams water. Stir to combine. Cover the bowl and let sit for 3 to 4 hours or until… … the surface of the dough is dimpled with air pockets. Add 360 grams water. (This part is really fun … the poolish bubbles up as a unit and floats on top of the water… it really feels alive!) Stir to combine; then add 12 grams salt and stir again to combine. Add 450 grams flour, preferably bread flour. Using a spatula, stir until you have a sticky dough ball. Cover and set aside for 30 minutes. With wet hands, perform a set of stretches and folds, by grabbing one side of the dough, and pulling it up and to the center. Rotate the bowl a quarter turn, and repeat the grabbing and pulling. Do this until you’ve made a full circle. (Watch the video for more guidance. I employ a sort of “slap and fold” technique, which is helpful with this very wet dough.) Cover the bowl. Thirty minutes later, repeat the stretching and folding. If time permits, repeat this stretching and folding twice more at 30-minute intervals. This is what the dough looks like after the third set of stretches and folds: This is what the dough looks like after the 4th set. Feeling the dough transform from a sticky dough ball to a smooth and elastic one is really cool. Transfer the dough to a straight-sided vessel and let it rise at room temperature until… … it doubles in volume. (Note: If you don’t have a straight-sided vessel, you can simply let the dough rise in a bowl. I personally like using a straight-sided vessel because it allows me to see when the dough has truly doubled in volume.) Then, punch down (deflate) the dough — I like to remove the dough from the vessel … … and ball it up using wet hands. Return the dough to the vessel; then transfer to the fridge. (Another plus of using the straight-sided vessel is that it’s easier to store in the fridge than a bowl.) The dough will likely double in volume overnight in the fridge. Remove the dough, turn it out onto a work surface… … then ball it up. (Note: This is where I deviate from the traditional ciabatta-making method. If I were to follow the traditional path, I would have simply patted that blob of dough pictured above into a rectangle; the cut it in half. I find I get a more open crumb when I preshape the dough.) Divide the dough into two equal portions. Ball up each portion. I like to do this with very little or no flour — I find I get better tension with less flour. Sprinkle a work surface liberally with flour. Place the balls top-side down (the smooth side); then sprinkle the balls liberally with flour. Cover with a tea towel and let rest for 2.5 hours. Line a sheet pan with parchment paper. After the 2.5 hours… the dough balls will look like this: Turn the balls back over… … then carefully transfer them to a parchment lined sheet pan. Bake at 425ºF for 20-25 minutes or until nicely golden: Let cool at least 20 minutes before slicing.

How to Make Ciabatta Rolls

Follow the recipe as outlined above or in the recipe box below until the step in which you remove the dough from the refrigerator; then, sprinkle a work surface with flour. Turn the dough out, sprinkle the surface with more flour, and pat it into a rectangle. (Note: This method, unlike above, follows a traditional ciabatta method — there’s no preshape or final shape. I prefer doing this with rolls for simplicity. It’s nice not having to ball up 8 portions of dough. If you wish, of course, you can ball up each round of dough.) Divide into 8 portions. Transfer to a sheet pan, cover with a tea towel, and let stand for 2 to 2.5 hours. Transfer the pan to the oven, and bake at 425ºF for 20 to 25 minutes. Let cool for at least 20 minutes before halving or slicing. 5 from 94 reviews

Notes:

As always, for best results, use a digital scale to measure the flour. I have had success using all-purpose flour, but if you can get your hands on bread flour (I use King Arthur Flour Bread Flour, which is 12.7% protein), that is ideal, especially if you live in Canada or abroad. If you live abroad or if you live in a humid climate, this may take a try or two to get right — I suggest making it once as written; then reducing the water by 50 grams or so depending on your results.) I find a bench scraper particularly helpful for this recipe. I also really love using a straight-sided vessel (with lid) both for letting the dough rise and storing it in the fridge.